Life Cycles

Some thoughts on bikes and the failed conventional wisdom of cycling policy.

The Tour de France reaches Stage 12 today and down he country lanes of England men are decked in lycra apparently enjoying themselves. A personal milestone set me off thinking about cycling, what makes it fun, what puts people off and why policy makers chase rainbows in this field more than most. I start with a personal journey, wander through the policies I’ve worked in set out why I think we get it wrong, not totally, but quite a bit.

I was talking to a reader about Golfing in the Red Wall and he said what he liked was you never know what you are going to get. Maybe next time I’ll write about something simple - like the Middle East. Meanwhile, enjoy.

I’ve been receiving video clips of my four year old grandson riding his two-wheeled bike without stabilisers or visible support. His Dad seemed more excited than he was, but that’s so often the way isn’t it.

I’ve had five bikes in my lifetime – which isn’t a lot. A few days ago I took the last of these to a local charity to recondition and do what they will with. It didn’t owe me anything, being something like 35 years old it’s done a load of miles. I hope whoever gets it enjoys it, or is even use it to work. I won’t be having another bike, that’s cycling done for me for physical reasons I won’t bore you with – there are some things you can’t fight forever.

I remember four of my five bikes fondly and I always enjoyed the freedom being able to get on the bike and go somewhere under my own steam provides.

My first was an old style Raleigh tricycle.1 The wheels seemed big but I was small. I was stable and I would go up and down the street happily. When I was about six I got a two wheeled job with little stabiliser things. It took me about two years to get rid of them, balance was never my strong suit, but it got me to school and round the streets – another Raleigh. It was red and gold, it had three gears in a hub and I loved it. But by the time I was getting too big for the frame bikes were colliding with fashion and reaching a crisis point.

I must have been ten and the Raleigh Chopper was the bike to have. A creature of the late ‘60s, the Chopper bicycle was inspired by the modified (chopped) Harley Davidson Hydra-Glides as ridden by counter culture icons Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda in the movie Easy Rider.2 Even though the Chopper was designed before the movie was released it’s success was totally dependent on the film. It was as simple as this – cool kids had Choppers, and who doesn’t want to be a cool kid. But looking at the extended forks and sat back riding position I didn’t think I would get on with one and falling off isn’t that cool. Obviously, my parents agreed, so instead of something better like a racing frame or another good town bike3 I ended up with some horrible slightly Chopper-like compromise that was the antithesis of cool. My third bike was the cycle equivalent of having Winfield trainers in which you would not wish to be seen dead instead of Green Flash.4 I rapidly lost interest in cycling.

The cycling gap in my early teens ended when I got my first evening job and, rather than spending wages getting there I invested in a Halfords Apollo, green hybrid town bike with dropped handlebars and derailleur gears. It got me pretty much anywhere I wanted to go, except school that is. My school was built with a vast area of bike sheds and stands, but we were not allowed to bring bikes to school and park them in those sheds. I’ve still no idea why. The Apollo eventually moved south with me, definitely my best bike. Unfortunately, after college and during my first job it was stolen (though I kind of know who took it) at about the same time I got my driving licence and so I wouldn’t be needing it.

The main difference between using a bike and not using a bike was weight gain. Bikes keep you fit and cars are really bad for your health, your back, and I dare say a whole lot of other parts, but they are and were aspirational and if a bike meant a degree of personal freedom a car was the real deal. My family didn’t have a car, I did, so that was going up in the world. And that was me for the next ten years or so until I decided the weight gain was becoming unacceptable and a bit more exercise was required. Anyway, by then mountain bikes were trendy. I’ve had a habit of picking houses at or near the top of a hill, or in the case of my current place, on the side of a fairly steep valley, so my intent to use the bike never really matched reality even though 21 gears helped a bit.

Policy wonks deny it but this really is one of the problems with the UK and cycling – with the exception of East Anglia we are a generally hilly place. The cycling countries,5the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, Hungary, Finland, Denmark and Belgium, are in large parts flat, at least where people live. When it’s flat, going to work or meetings or the shops on you bike is a no brainer. When it involves hills and sweat and showers and getting covered in mud and who knows what else it really isn’t. This is the most basic reason why cycle commuting gets stuck between 2% and 4% of journeys.6

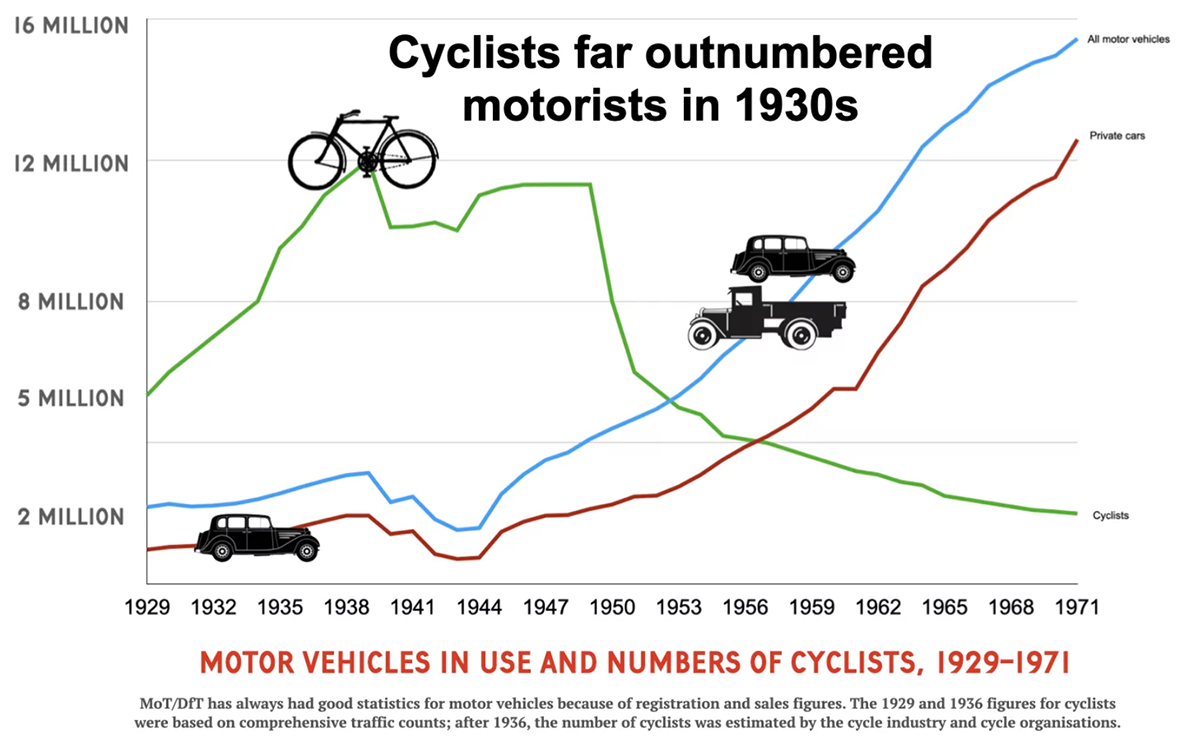

Nonetheless, more people routinely ride bikes these days than did when I was scooting around on my green Apollo. At that time there were few designated cycle lanes, no segregation, no measures to create priority and it was definitely a very bad thing to cycle on the pavement, rightfully and legally the preserve of the pedestrian. Indeed the 1970s were probably the low point for cycling use. What had been a ‘majoritarian’ means of transport in the 1930s declined with the rise in affordable and popular car ownership from the 1950s. Bikes were all very well, but they were the transport of the past, people had voted with their seats, so what was the case for investment in cycling infrastructure? This may have been short sighted, but it was still evidence guided policy of a sort.7

So what was it that gave cycling a bit of an uplift after the trough of the 1980 and 1990s? Was it a few disconnected cycle lanes or was it fashion? Was the renewed interest in cycling about hard or soft investment? I argue that it was very much the latter. Just at the end of each June I would see boys and girls chalking out tennis courts on the road and padding balls back and forth for a week or two, now each year when the Tour de France kicks off the country lanes fill with men in lycra. Cycling’s media reach became greater as British cycling’s performance improved. Chris Boardman’s gold medal in Barcelona was the initial breakthrough but the winning performances on road and track of the likes of Bradley Wiggins, Chris Froome, Laura Trott and their ilk gave recreational cycling a profile boost nothing else could. Being a cycle sport person in France or Belgium was always a normal pastime, part of the culture, for Brits not so much. It’s to the good, mostly, because the fitness benefits are significant and cycling is much safer than most people believe (but see below). Even though hard statistics on cycling are fiendishly difficult to interpret, the indications all point to an increase since the 90s in recreational/fitness cycling and a broadly level share of work trips.

For the transport planners, however, the prize is not people going out for a ride in the evening or at the weekend, it’s the commuter journey, or the journey at other peak times of congestion. In this field the there was evidence of some small shift but for many years now most independently sourced figures show the proportion of cycle journeys static. There are several issues here: first, even government figures are contradictory, figures from cycling industry or pressure group sources tend to show greater usage. This helps nobody. Second, it is clear that bike usage depends on the nature of the journey. A trip of less than two miles relatively flat urban journey, fits nicely with a bike: quicker and easier rather than waiting for a bus, walking to a station or sitting in congestion and struggling to park a car. Depending on the terrain and the alternatives, cycle journeys of up to five miles can be attractive, especially where driving is difficult. Longer, less level journeys make no sense other than for the ultra fit. (I did know a man who routinely travelled from Buxton to Stockport by bike – 18 miles, 760 feet climb – but he was a tech guy).

Under the Johnson government the DfT published a target to “double cycle journeys”,8 yet the evidence, such as it is, suggests that it is especially difficult to track cause and effect and whether there is anything positive a government can do that will have much impact – “Field of Dreams”was never a much of strategy.9 Even then, doubling a very small number is all very well but the overall impact is still a small number.

But indeed, the Johnson Government got its wish in 2020 cycling doubled, but that was all about people not going to work. The Covid lockdowns, as ever, prove everything and nothing. Cycling was one of the few ways to get out and about during lockdown and one of the only realistic ways of getting exercise when gyms and swimming pools were closed. Even I went out on my bike a few times. It was also in the open air. The tube/bus/train had always been somewhere to catch cold, so wanting to avoid public transport during the pandemic was entirely rational. After the pandemic, slowly but surely, the population assumed its former habits while cutting out some commuter journeys altogether. Cycling seems to have settled back a little below pre-pandemic levels10 – because cyclists can work from home too. Nonetheless, we can probably all agree that more people getting more exercise is a good thing with societal benefits.

When I was responsible for Transport in a unitary authority I was thought by some to be against promoting cycling. This was despite the fact that my tenure saw a greater expansion in cycle facilities in the Borough than at any time before or since and a decent number of photo calls to publicise bike weeks and the like. We also did quiet things, like understanding that if there is nowhere to park a bike it’s a problem, so we installed a lot. What I was against, and I suggest this is good advice to anyone interested in seeking positive change in transport, was preaching to people about how they should live their lives and telling those who just want to get in their car to go to work that they are somehow ‘bad people’.

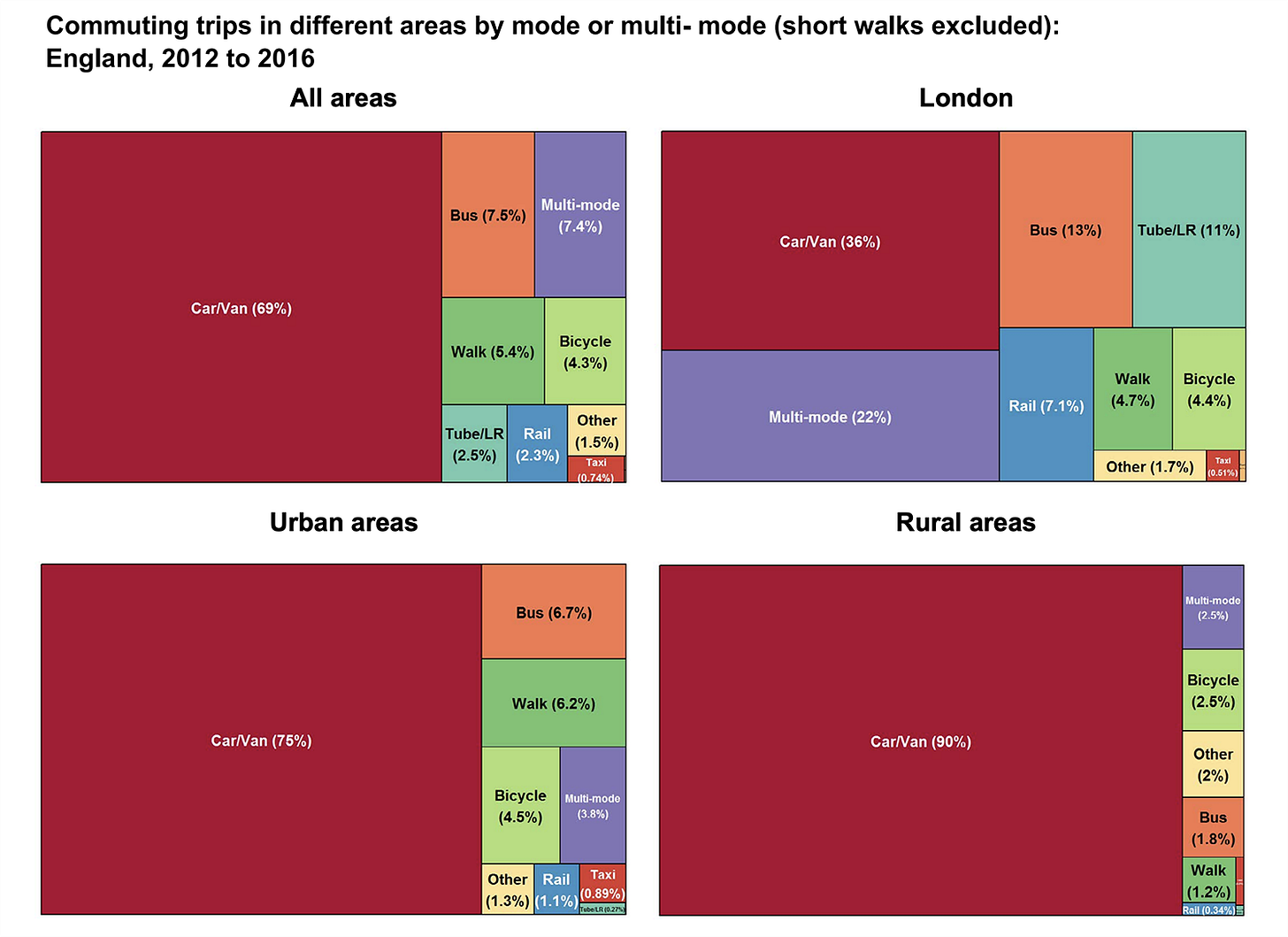

A simple glance at the commuting statistics should make it clear why ‘anti-car’ messages are utterly stupid – two out of three people travel to work that way.11 People will never be won over by being told they are behaving badly, yet politicians and bureaucrats have continued to phrase their transport messages in patronising and negative terms, easily categorised as ‘anti-car’. My approach focused on giving the travelling public realistic choices, enabling people to move more easily and improving and promoting public transport, through which we were able to nudge more people in a positive direction. Then in the late 2000s something stirred.

There has always been, in the ideological undergrowth, an obscure and pointless discussion about whether cycling is inherently right or left of centre. Broadly speaking thats, personal freedom and individual choice vs democratic, affordable travel. Onto and across those notions is laid the environmental benefit of cycle vs powered travel (social) and health benefits (individual). This is fabulously bonkers on every level, first of all because all of these things can be true at the same time, but especially counterproductive when veneered with a coating of moral superiority. It is that notion, that cycling means you are a better person who has made morally superior choices that alienates, well, just about everyone else. This form of policy moralism is, in my view, most pronounced left of centre and an especially irritating form of the “good socialist/good environmentalist” paradigm. Dig deeper, however, and it all becomes just as strange and wonderful right of centre. Take this from a London cyclist writing where else but The Spectator:

“Cycling is the exclusive preserve of the very few and the very able. As for cycle lanes, which pander to a tiny and privileged elite at the expense of the vast majority, they’re undemocratic and wrong.

“This morning, as I sailed down a wide and empty cycle line, I agin felt my rucksack weighing me down with guilt and shame at the sight of those poor people alongside me; squashed against their will into 50% of the roads they paid for. Helpless, gridlocked and trapped by authoritarian policies which suggest that their time – their lives – aren’t as important as mine.”12

Where did all this ideology baloney come from? It’s possible to find all sorts of rubbish if you delve deep enough in old pamphlets, but a lot has moved on since then. Some of this stuff seemed to resurface around in David Cameron’s time in opposition.13 The same time he was doing hug a husky,14 and deciding what his party needed was a green tree. I suspect it for an internal audience, telling them “it’s OK to be in favour of non-car transport” and to accommodate Boris Johnson’s claiming credit for the London bike hire schemes.

Fact lite prejudice the Spectator quote may be, but there are several elements car drivers witness anecdotally that support that view. Many dedicated cycle lanes, particularly along roads built in the last 40 years, appear to be empty. Dedicated cycle lanes have been built into road improvement plans whether there is any indication of likely demand on the route because the funders insisted on cycling infrastructure as part of the project – a sustainability tick box, if you like. In reality this would have very little impact on the overall costs of the project. It was at the margin of something being built anyway and often as segregated pavement. Delve into the history of cycleways and you will find, pretty quickly, that road construction in the 1930s routinely built cycleways alongside new roads which were either later incorporated as a ‘hard shoulder’, a footpath or a carriageway widening. Those presenting the projects will often try to separate arbitrarily the cost of the cycling element as a means of convincing the cycling advocates that they are served by the project, yet not building the cycling element wouldn’t save the sums identified.

What I find exasperates people driving most is not the cycleways themselves, but the sight of a cyclist using the main carriageway when there is a dedicate cycle lane available. This is closely followed by those in the middle of the road after dark without lights, ignoring traffic signals, one way streets, cyclists on country roads who ride several abreast, seemingly deliberately to hold up traffic, and the notion of cyclists with video recording cameras filming vehicles. The last two are debatable, but even though there can been valid reasons (maintaining momentum is a thing), the non-use of available cycle lanes is not a good look. 2016 figures found 59% in agreement with the statement “It is too dangerous for me to cycle on the roads”. That was a drop from 64% the previous year and is a very significant perception. Unfortunately it is also significantly disconnected from reality. In 2016, 2668 adults and 317 children were killed or seriously injured (KSI) while cycling in the UK. It might sound a lot and it is always too many, but in fact it is a tiny number - 4.62 for each parliamentary constituency in the land. Overall cycling fatalities were just over a hundred nationwide.15 While minor accidents are underreported KSI accidents are not. If you are involved in an accident while cycling you are still nearly two and a half times more likely to become a KSI statistic if you are cycling at the time.16 Over time cars have become much safer, bikes have not, mainly because they can’t, in that light the complaint about non use of available segregation facilities seems to me a reasonable view.

As ever, the media doesn’t help with its clickbait columnists and lazy stereotypes peddling half truths. People who drive do not, by and large “hate cyclists”, even if they do become irritated by the behaviour of some cyclists, largely because more than one in three people who drive also cycle. People who cycle do not, by and large, “hate people who drive”, though they do get irritated when drivers fail to take account of people cycling, not least because almost all people who cycle have a driving licence and the vast majority drive from time to time – like, I don’t know, Jeremy Clarkson.17 But that doesn’t make a story, does it, however, the behaviour of some ‘ultras’ on either side provides all the standing up they need.

So what would make for better policy outcomes?

Cycling has to be cool. Bikes have to be cool. For too long cycling policy has been the province of the eccentric. Knock the ideology thing on the head and stop going on about the environment. Appeal to fitness and fun.

Get rid of the term ‘motorist’. What is a ‘motorist’ these days? A person who supports the ideology of motorism? This might seem trivial, but what I’m really getting at is the tendency of journalist to seek comment or consume press output from ‘motoring organisations’. The notion the the AA and the RAC represent the views or interests of anyone other than themselves as service providers is entirely bonkers. The notion of the ‘motorist’ is also one that ignores the reality – people who drive, sometimes also ride bikes, catch trains and even sometimes walk to the shops.

Policy makers should ignore cycling campaign groups for the same reason. These are always self-appointed ‘ultras’ who are entirely unrepresentative of the wider group of people who ride bikes. If you want to find the people not using the available cycle land you will find them in these groups.

Don’t believe the article of faith that sees increasing cycling as a serious transport solution in the UK. Improving cycle facilities will never bring about the kind of modal shift that can make a significant dent in commuting traffic and road congestion. It can’t, it hasn’t, it won’t. Doing the same things over and over and expecting a different result is madness.

With those things flushed out of your head, continue to invest in cycling, bearing in mind that soft measures can be just as effective as engineering solutions. Find quiet routes and build networks, not based on the line of a new road, but based on where people want to go and can easily connect with. Build recreational rides and promote fitness.

Understand that ‘driverless’ technology is the cyclist’s friend. A car’s sensors are and will be far better at detecting a person on a bike than humans ever will. Many of the cars which incorporate such technology are those cycling ultras seem to hate most – another reason to ignore them.

Recognise that those who ride bikes irresponsibly are a danger to themselves and others and should face sanction where practical. Where there are dedicated cycle lanes cycles should be excluded from the rest of the carriageway.XX People driving worry about the unpredictable movement of cycles, just the way people cycling worry about the unpredictable movement of pedestrians on shared infrastructure. People driving feel they will always get the blame when something goes wrong.

Recognise that cycling is not an accessible transport mode and cannot ever be – it is almost exclusively for the able bodied.

Slow traffic down and reduce access where necessary. Stress the safety aspect –there is tons of evidence, so don’t talk green. This matters much more to pedestrian safety, where more people become KSI statistics than on cycles, but it’s important to everybody. Britain has had an excellent road safety record. That has slipped a bit – we should be making this a matter of national pride.

Being effective in transport policy involves challenging the conventional wisdom. Seeing the same thinly supported arguments about encouraging cycling while the dial hasn’t really moved has been frustrating. Although I’m done with riding myself, I must admit I will miss it. There was no better way of getting out of the chaos after Reading FC’s home games that belting into town on the A33 cycleways miles ahead of the traffic.

Before I finish, just a word about London. Cycling in London has certainly increased. Infrastructure has been part of the picture, but that must be combined with the sheer impracticality of using a car, the cost of parking a car and the hugely successful policies that have taken traffic out of much of the capital, including public transport improvements. Many fewer people bother to get a driving licence than elsewhere in Britain, but there is also the cost of living in London. When housing is such a huge part of the budget something else has to give and the next biggest budget line is usually personal transport. As ever, London isn’t England, London is London.

That’s all for this week.

Thanks for reading.

Till next time, take care

John

My parents were big with market leaders.

Easy Rider, Columbia Pictures 1969. Made for $400K, box office $60 million. Ye ha! That buys a whole lot of drugs and Dennis Hopper set out to do just that.

I always wondered why my Dad didn’t try to talk me into this. Come to think of it, I never saw him ride a bike.

This is a 1970s thing. In 1971 Dunlop Green Flash were the gym shoes to have - like Nike Air whatever these days. Winfield was the own brand of Woolworths.

Meaning those with cycling as a main personal mode of transport - see Euronews here.

National Travel Surveys - UK Government.

There is a little history of all this here at British Cycle Tracks

“Build it and they will come”

Gov.uk Cycling Factsheets 2020-22

Analysis from National Travel Surveys. DfT

“Of course cycling is right wing”, Paul Burke, The Spectator. 14 December 2020 Paywalled.

There is a piece on an old BBC News site delving into this from 2008 here. It’s crackers.

Not a hoodie - he did that too.

Sustrans - Key walking and cycling statistics for the UK, published 2018 Sources from NTS and DfT

My calculations based on the figures quoted by 15 above and the total KSI figure from DfT for 2016 - 25,511. So 2668 adult and 317 children - 2985/25511 = 11.7% of KSI based on 4.3% of journeys. While 73.2% of KSI are in other vehicular modes (total less 2985 and 3851 pedestrian KSI/total) accounting for 69% of journeys. So 2.72 plays 1.06 = 2.56

Mr C claims he got a a bike to lose weight, and did. Not tht there is much evidence of that in the latest season of Clarkson’s Farm (which is not as funny as the others).